A Station Trapped in the Past

In the heart of Manhattan, Penn Station stands as the busiest rail hub in North America—yet also the most hamstrung.

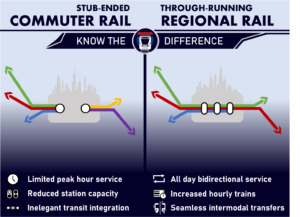

Every weekday, hundreds of thousands of riders converge on its platforms, boarding or disembarking from Long Island Rail Road, NJ Transit, or Amtrak services. For all its size, the station betrays its purpose: instead of creating fluid, cross-regional connections, Penn Station largely functions as a dead-end terminal that forces trains to halt, unload, and reverse. It’s a system designed decades ago, squeezed into the 21st century without the modern integration found in global cities like London, Paris, and Berlin.

Compounding the frustration is a $16.7 billion Penn Station Expansion plan—often referred to as Penn South—that does nothing to address these outdated operations. Instead, it seeks to add more stub-end tracks to a station already hobbled by its terminal model.

Critics argue the real solution is through-running: letting trains flow from one side of the region to the other, with Penn Station merely a midpoint. According to leading transit advocates, a comprehensive reengineering of station tracks, signals, and governance—costing roughly $10 billion—could unleash Penn Station’s untapped capacity and revolutionize the daily commute for hundreds of thousands. But institutional inertia, political showmanship, and turf wars continue to stand in the way.

The Bottleneck at America’s Busiest Rail Hub

Stand on a platform at Penn Station during rush hour, and you can almost feel the system choke under its own weight. Trains heading into Manhattan linger for extended dwell times—15, 20, sometimes 30 minutes—while passengers scurry onto chaotic platforms, hurrying to catch connecting trains in the same building. Each train’s prolonged presence ties up scarce platform space, preventing the next arrival and creating a chain reaction of delays and congestion.

Those forced to switch from NJ Transit to LIRR trains or vice versa often must navigate separate concourses or even re-enter the station complex, a labyrinth that saps time and energy. Rather than serving as a powerful through-corridor for the region, Penn Station operates as three distinct railroads simply co-located under one roof, each with its own equipment, labor agreements, and track rights.

The constraints at Penn Station ripple outward, limiting train frequencies and forcing agencies to run fewer peak-hour trips than the station’s theoretical capacity could support. This outdated design—rooted in the era of steam locomotives and siloed commuter rail lines—has persisted for generations, and it directly undermines the speed, reliability, and connectivity that modern passengers expect.

How to Scale Up the Problem

The official “fix” on the table is the $16.7 billion Penn Station Expansion, commonly dubbed Penn South. At first glance, adding more tracks appears a logical solution for a crowded train station. Politically, it’s also an easier sell: new, high-visibility projects bring major construction contracts, union jobs, and photo-worthy groundbreakings.

Yet building additional stub-end tracks is akin to widening a one-lane ferry dock without rethinking the fundamental approach. Trains would still idle, reverse, and navigate the same cramped station throat interlockings.

Advocates of Penn South contend that extra capacity could marginally reduce platform crowding and allow more trains into Manhattan. But skeptics note that the underlying “enter-and-reverse” model would persist, capping the station’s real potential. In practice, each track extension at a dead-end station only shifts where the clogging occurs, rather than removing the choke point.

While Penn South’s supporters often celebrate an eventual “new station” with a fresh building footprint, critics warn it’s a 20th-century solution to a 21st-century mobility challenge. At a budget approaching $17 billion, it promises minimal operational improvement for the cost, without addressing the structural flaws of terminal-based operations.

The Case for Through-Running

Through-running transforms a station from a destination into a pass-through. Instead of trains terminating at Penn Station, they would continue onward—connecting Long Island to New Jersey, the Hudson Valley, or beyond. Global transit powerhouses have embraced through-running for decades:

- Paris RER: Suburban rail lines penetrate central Paris through connected tunnels, delivering cross-city journeys with minimal transfers.

- London’s Elizabeth Line (Crossrail): Tunnels under central London unify suburban routes, massively boosting capacity while reducing travel times.

- Philadelphia’s Center City Commuter Connection: An 1980s project linking two separate commuter rail terminals into one continuous corridor, demonstrating that run-through service can flourish in American cities, too.

By eliminating tedious turnbacks, through-running both cuts platform dwell times and increases overall track capacity. The station effectively becomes a corridor where trains enter from one side of the metro area and exit on the other. Passengers save time, avoid extra transfers, and enjoy more direct journeys—key benefits in an age when labor markets are spread across multiple states.

A $10 Billion Path to a Fully Integrated Penn Station

Analysts suggest that $10 billion—significantly less than Penn South’s $16.7 billion—would enable comprehensive through-running at Penn Station. That cost includes:

- Track & Platform Reconfiguration (~$3.0B)

Rebuilding platforms and track layouts for continuous flow, installing new crossovers, and eliminating design features that trap trains in stub-end tracks. - Signal & Technology Upgrades (~$2.0B)

Deploying advanced train control systems, such as Communication-Based Train Control (CBTC) or an advanced Positive Train Control (PTC), to increase train frequency and safety. Equipping dispatch centers with unified scheduling software for real-time adjustments. - Station Capacity & Passenger Flow (~$1.5B)

Modernizing concourses, stairways, and vertical circulation to accommodate higher volumes of riders transferring quickly between lines. Streamlining platform access and signage. - Rolling Stock Adaptation (~$1.0B)

Modifying LIRR and NJ Transit fleets for compatibility across each other’s tracks. Adjusting door heights, power systems, and onboard equipment to ensure cross-territory running. - Labor & Governance Reform (~$2.5B)

Harmonizing union contracts, pay scales, and operating rules among three commuter railroads—LIRR, NJ Transit, and Metro-North—so trains can cross boundaries without complex crew changes or equipment restrictions.

Far from an abstract plan, much of this blueprint simply aligns with best practices in global rail networks. The biggest obstacles are less about engineering and more about politics, cost sharing, and institutional clout. But at a cost lower than Penn South, the payoff in added capacity, better reliability, and fewer forced transfers could be transformative.

How Through-Running Could Transform the Region

Penn Station’s inefficiencies ripple across the entire tri-state area, touching riders from Long Island to New Jersey to upstate New York. A modern, run-through station would create:

- One-Seat Rides Across State Lines

A commuter in Hempstead could reach Montclair without an extra subway or concourse dash in Manhattan. Someone in Newark could travel directly to Jamaica or beyond into Nassau County, saving 20 to 40 minutes each way. - Higher Train Frequencies

With platforms freed from lengthy dwell times and turnbacks, more trains could run during rush hour, offering subway-like headways in some corridors. - Reduced Congestion and Less Road Traffic

As trains become more attractive and reliable, fewer commuters would rely on highways or subways to hop between suburban rail lines, easing stress on major roads and tunnels. - A Unified Regional Economy

Linking suburban communities across the region fosters job mobility, spreads housing options, and narrows the divide between historically disconnected labor markets. The entire corridor—from Poughkeepsie to Ronkonkoma, Stamford to Trenton—would feel more integrated. - Long-Term Operational Savings

An integrated system avoids the expensive redundancies of maintaining separate fleets, staff, and yards. Over time, that synergy could yield lower operating costs.

The Meadowlands Football Train—A Fumbled Opportunity

Though often overlooked, the Meadowlands Football Train Pilot—nicknamed “Train to the Game”—offers valuable insights into the systemic hurdles that continue to undermine genuine through-running progress at Penn Station.

Launched in 2009, this service exemplified the promise of multi-agency cooperation: it connected Connecticut and Westchester directly to the Meadowlands Sports Complex via Metro-North, Penn Station, and NJ Transit, marking the first tri-state rail collaboration of its kind.

Initially championed by Metro-North President Howard Permut, the pilot required minimal infrastructure investment and delivered 5,826 total rides over its inaugural season, averaging 647 passengers per game and generating $67,727 in revenue

Metro-North President Howard Permut

“This test of regional integration took several years of planning but only minor investment in infrastructure.

We think this tri-state train service—a first in the century-long history of these three railroads—will be great for football fans.

No traffic, no parking lot jam-ups and a safe, easy ride will make getting to and from the games a breeze. I hope it catches on.”

Yet even with such encouraging beginnings, operational and administrative barriers came into stark relief. The pilot depended on NJ Transit’s trains, limiting Metro-North’s influence over scheduling and forcing a few narrowly timed Sunday departures.

Lengthy travel times—nearly three hours from New Haven—and a convoluted handoff at Penn Station bogged down the service. Agreements for crew changes, insurance, and revenue sharing were similarly complex, further eroding efficiency.

“Last year, just 1,568 fans rode the trains to 10 games, said railroad spokeswoman Marjorie Anders. “It is not wildly popular, but we believe it will catch on eventually,” she said.

But to the railroad, it’s more than just an added service for sports fans; it’s a look at how trains can offer more regional services.“It’s a service that proves that it’s possible for New Haven Line trains to run all the way to New Jersey,” Anders said. “It’s kind of an investment in the future.”

September 10, 2014 – “Train to the game: Metro-North draws Giants, Jets fans”

By 2016, ridership had sunk to an average of 197 passengers per game, and the pilot was quietly discontinued—its once-trademarked “Take the Train to the Game” slogan canceled.

Of particular relevance as Penn Station’s through-running debates intensify are the institutional silos that contributed to the Football Train’s short lifespan. Divergent budgets, discrete equipment pools, and distinct labor rules among the MTA, NJ Transit, and Amtrak all overlapped, hampering coordinated service and underscoring governance gaps. A persistent lack of unified oversight also compounded financial and administrative burden.

Taken together, these realities mirror the very same challenges that have slowed or derailed proposals for cross-regional through-running—challenges that some railroads appear content to let persist in favor of advancing a Penn South expansion through the NEPA process.

In the end, the Meadowlands Football Train stands as both a case study and a warning. It offers a glimpse into what inter-agency cooperation could achieve if the structural obstacles were truly addressed and if all parties fully embraced a regional perspective.

As the conversation around through-running continues—and as certain railroads steer resources and influence toward their favored Penn South project—policymakers would do well to remember how quickly an ambitious, cost-effective pilot can vanish without a firm, integrated foundation to sustain it.

The lessons of the Train to the Game must inform every facet of ongoing and future cross-state rail efforts at Penn Station.

Why Isn’t Through-Running the Default?

1. Construction Contracts and Political Theater

Major station expansions, especially $16.7 billion proposals like Penn South, garner more attention, bigger construction deals, and splashy media coverage than the less glamorous but far more beneficial approach of integrated operations. Elected officials often find new “megaprojects” easier to sell to constituents than intangible operational reforms.

2. Labor and Union Negotiations

Unifying LIRR, NJ Transit, and Metro-North workforces under a single operational framework demands a political heavy lift. Each union has entrenched seniority systems, different pay scales, and unique work rules, making a merged structure formidable but not impossible.

3. Institutional Silos

Turf wars between separate agencies—some governed by New York State, others by New Jersey, plus Amtrak’s federal oversight—create a thicket of conflicting agendas. Getting them to coordinate timetables, rolling stock, or even platform assignments can require months or years of negotiation.

4. “This Is How It’s Always Been Done”

Penn Station’s original design as a stub-end terminal has become a self-fulfilling blueprint for half a century. Many mid-level managers and senior officials have built careers optimizing an inherently flawed model rather than championing a radical overhaul.

Contrasting Success Abroad—and the Perils of “Show Me the Market”

European cities have already demonstrated that skeptics who claim “there’s no market for cross-regional service” may simply be missing latent demand. London’s Thameslink is a striking example. In 1988, British Rail revived the disused Snow Hill Tunnel, bridging north and south London with a new cross-city service.

Initially, some top managers were unconvinced: “Show me the market,” one famously said, according to a contemporary Daily Telegraph piece. Yet once Thameslink opened, ridership soared far beyond projections. Within a year, British Rail committed to more than doubling the initial £70 million ($240 million in 2023 U.S. dollars) investment to handle skyrocketing passenger demand.

That story resonates powerfully with Penn Station’s predicament. Too often, agencies treat “demand” as a static metric—if ridership isn’t already high, they conclude it’s not worth the investment. But real-world success stories like Thameslink show that when travelers are offered a direct, frequent, and reliable path, the market materializes.

The danger lies in letting outdated frameworks, risk-averse planning, and short-term cost savings overshadow the potential for transformative gains in mobility and economic vitality.

Overcoming the Status Quo

1. Build Public Momentum

Grassroots advocacy is crucial. Riders, civic groups, and local businesses should demand integrated operations over flashy expansions. Writing op-eds, attending public meetings, and pressing elected officials to consider the $10 billion through-running plan can shift political priorities.

2. Legislative Leadership

Governors and legislatures in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut must tackle labor reforms and unify budgets. The next capital funding cycles could mandate that new state funds for Penn Station improvements be contingent on track reconfigurations, cross-compatibility of rolling stock, and simplified labor contracts.

3. Federal Incentives

As the Northeast Corridor is vital to the national rail system, federal grants or loan programs can catalyze cooperation. Washington can reward agencies that unify timetables, integrate fleets, and reduce turnbacks at Penn Station.

4. Transparent Timetables and Pilot Projects

In the near term, agencies can launch small through-running trials with existing equipment—beyond just a Sunday football train. This can generate real-world data, build commuter familiarity, and identify the operational wrinkles that need ironing out before a broader rollout.

Building Connections, Not Dead Ends

Penn Station sits at the nexus of the nation’s busiest corridor, yet it persists in a terminal-based design that no longer suits the region’s sprawling labor markets and modern commuting needs. The $16.7 billion Penn South plan effectively recycles century-old thinking, piling on more dead-end capacity at tremendous taxpayer expense.

A more pragmatic and transformative approach lies in through-running—leveraging around $10 billion to reconfigure tracks, update signals, unify labor rules, and create a genuinely integrated tri-state commuter system. This blueprint aligns with global best practices and promises far more capacity for less money, delivering faster, more direct service from New Jersey to Long Island, the Hudson Valley, and beyond.

Yes, it will require forging new agreements, standardizing equipment, and confronting the “we’ve always done it this way” mentality. But the payoff is enormous: a truly modern Penn Station worthy of America’s greatest metropolis. The cautionary tale of the Meadowlands Football Train Pilot reminds us how quickly multi-agency cooperation can fizzle without permanent structural commitments.

By finally resolving institutional barriers and orchestrating a unified operational plan, leaders can ensure Penn Station does more than warehouse arriving trains. Instead, it could become the cross-regional nerve center that unleashes the full potential of commuter rail—leading to less highway congestion, better mobility, and a more unified economic engine for the entire tri-state area.

After decades of half measures, the moment for a genuine breakthrough has arrived. Shifting from bigger dead-ends to better connections isn’t just feasible—it’s financially smarter, internationally proven, and crucial for the region’s future. The only real question is whether the political will can align with public demand to reimagine Penn Station not as a terminus, but as a through-running gateway to opportunity and growth.

3 Responses

Very good https://is.gd/tpjNyL

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2