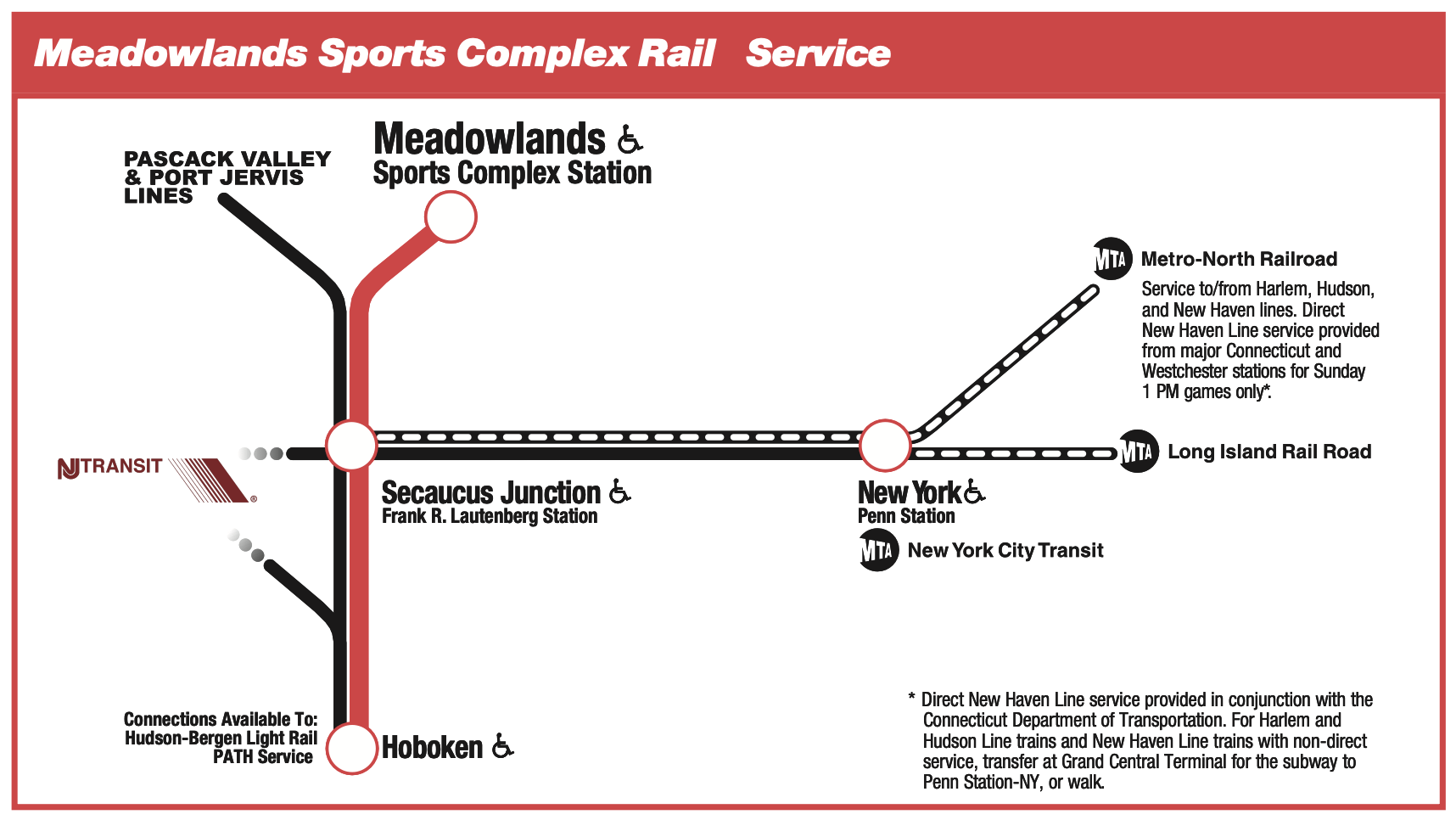

The iron wheels of an NJ TRANSIT coach, temporarily repurposed for cross-regional service, rumbled across the Hell Gate Bridge carrying Connecticut football fans toward the Meadowlands. For a fleeting moment between 2009 and 2016, this experimental service—operating from New Haven over Amtrak’s territory through Penn Station, where crews exchanged and the train metamorphosed into a regular Northeast Corridor Line service—embodied the tantalizing possibility of northeastern rail integration. After stopping at Secaucus Junction, passengers made a brief transfer to the frequent Meadowlands Rail Line shuttle, completing the final leg to MetLife Stadium through a choreographed transit sequence far more elegant than the usual multi-stage odyssey confronting regional football patrons.

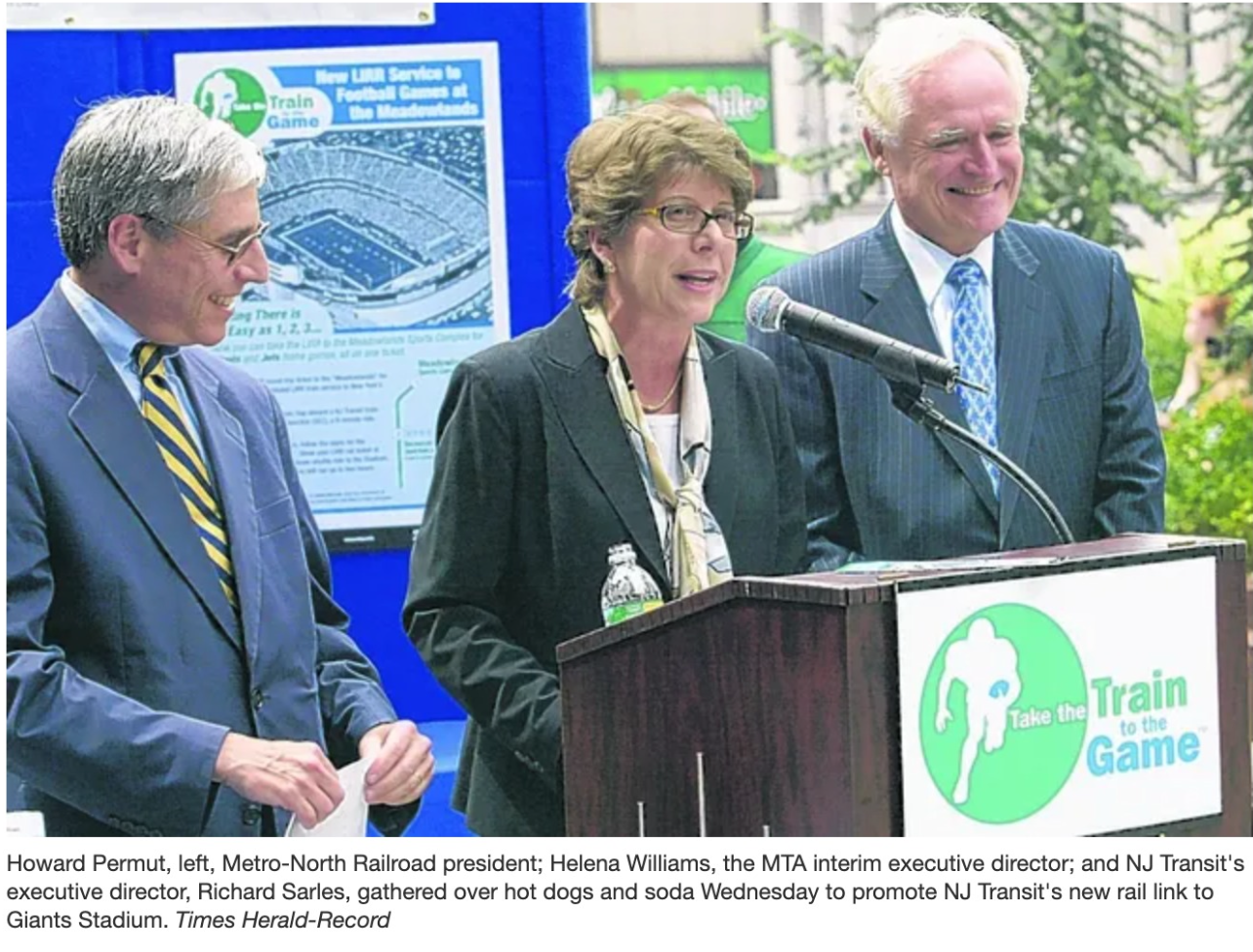

This delicate exercise in operational diplomacy emerged from an alignment of policy ambitions—Connecticut Governor M. Jodi Rell’s quest to extend Metro-North’s reach, persistent advocacy for regional rail harmonization, and improved stadium accessibility. What resulted was not the mythical “one-seat ride” sometimes misattributed to the service, but rather a carefully orchestrated connection sequence representing rare cooperation among typically territorial transit fiefdoms.

Yet within seven years, the service had vanished into bureaucratic obscurity. The cautionary tale of its collapse reveals an intricate web of factors—where fiscal exigency proved the executioner of an initiative already constrained by infrastructural limitations.

The special service initially offered a measured convenience—three pre-game trains from Connecticut and three post-game returns, primarily serving Sunday afternoon NFL contests. These operations demanded meticulous coordination between agencies: NJ TRANSIT equipment traversed Amtrak’s Hell Gate territory before negotiating the congested approaches to Penn Station, where additional passengers boarded before the journey beneath the Hudson River continued.

From its September 2009 inception, the service confronted Penn Station’s unforgiving spatial reality—a station operating at capacity saturation in North America’s densest rail corridor. Amtrak, as dispatcher and gatekeeper, maintained profound reluctance to surrender additional slots for these special trains, creating a structural ceiling on potential expansion. This bottleneck represented an ever-present constraint on the service’s development.

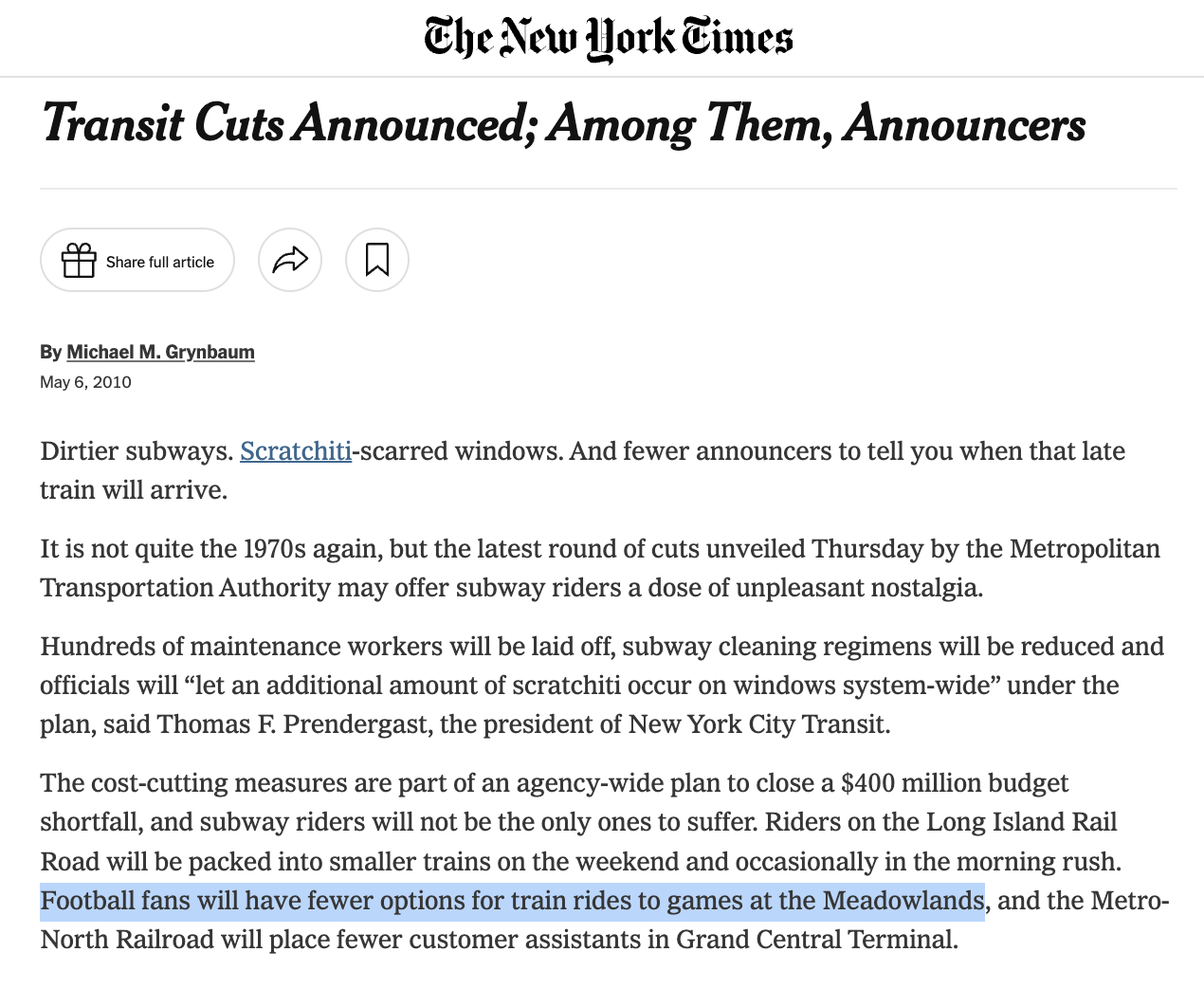

But infrastructure limitations alone did not orchestrate the service’s demise. The fatal intervention came through budgetary necessity in May 2010, when MTA President Thomas Prendergast unveiled sweeping cuts addressing a crippling $400 million deficit. Embedded within these austerity measures was a decisive declaration: “Football fans will have fewer options for train rides to games at the Meadowlands.”

This bureaucratic understatement masked a devastating contraction—reducing service from three trains to a single operation in each direction. This 67% service reduction eviscerated the program’s core appeal of scheduling flexibility during its critical developmental phase, fundamentally compromising its value proposition mere months after launch.

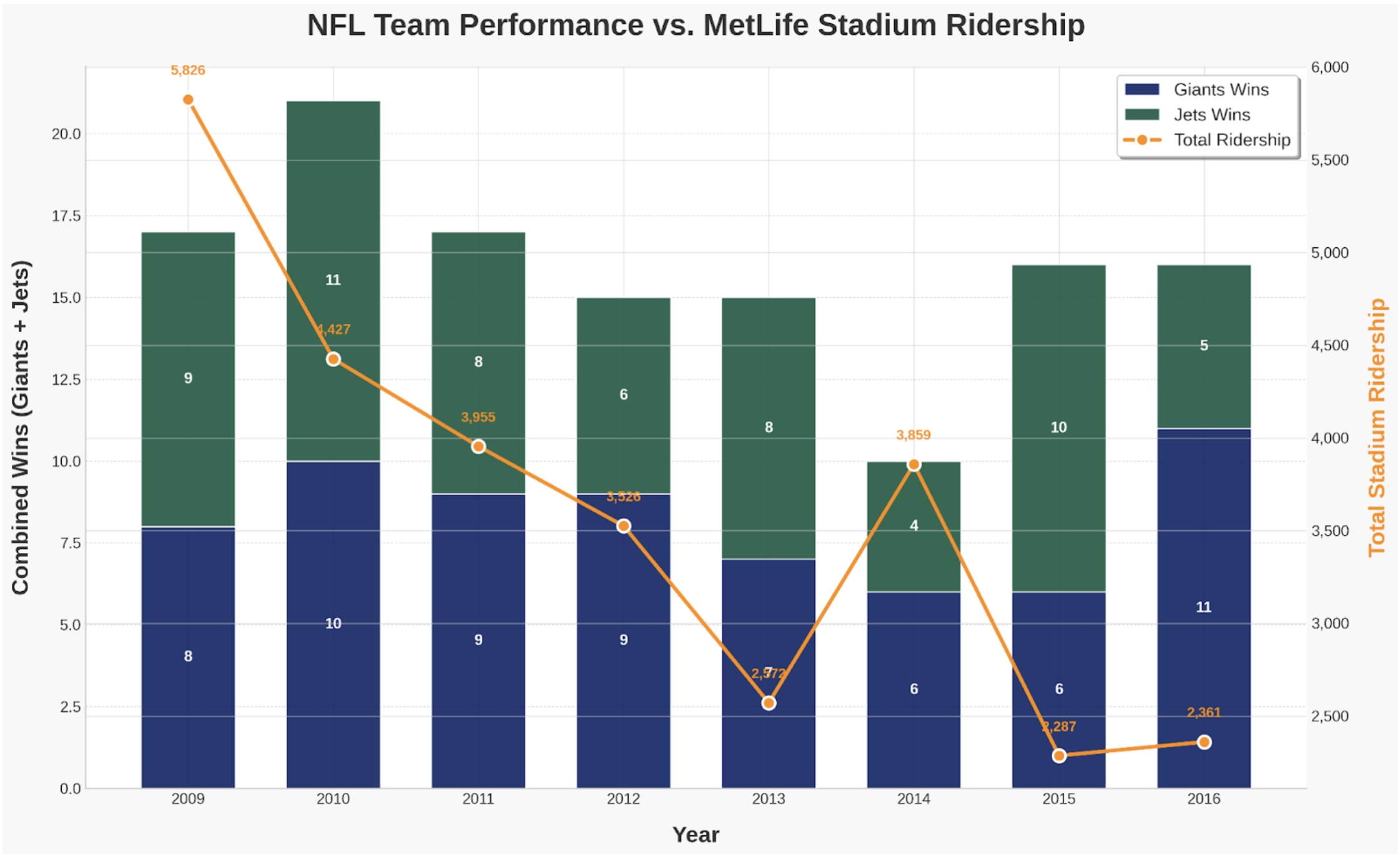

The service consequently entered transit’s notorious death spiral: the severe frequency reduction predictably diminished ridership, further undermining revenue generation, rendering the service increasingly difficult to justify amid persistent fiscal constraints. Each NFL season thereafter saw the initiative further marginalized within regional transportation priorities.

Operational realities compounded these structural challenges. Passengers reported extended delays during crew exchanges at Penn Station, confusing boarding protocols, and communication breakdowns. The technical interoperability enabling the service never translated into seamless passenger experiences—a critical failure in maintaining ridership loyalty.

Meanwhile, competitive alternatives proliferated. Ridesharing services offered increasingly convenient stadium access. NFL scheduling flexibility reduced predictable 1:00 PM kickoffs, further eroding the pilot service’s utility. Despite promotional efforts featuring former players, ridership remained modest, generally averaging 600-700 passengers per game—insufficient to justify continued operational investment during periods of fiscal constraint.

By 2017, the Meadowlands Train to the Game had disappeared without formal announcement. Amtrak’s “Summer of Hell” track renewal provided convenient institutional cover for its termination, but the service had effectively suffered mortal wounds years earlier through the 2010 budgetary intervention.

The experiment’s terminal breakdown during the 2014 Super Bowl—when thousands of fans overwhelmed the Meadowlands Rail Line shuttle after the game—evaporated most political support for event-focused rail service. This operational meltdown, which stranded passengers for hours outside in the middle of winter and in dangerous overcrowding conditions, crystallized for regional officials the system’s fundamental inadequacy for major events, though it’s worth noting that the Train to the Game service was not actually operational for the Super Bowl (only the shuttle segment between Hoboken, Secaucus, and MetLife–not the Metro-North New Haven Line through-running service). Regardless, this debacle continues influencing regional transit planning, with the Murphy administration now developing a multi-million dollar TransitWay, dedicated bus infrastructure aimed at doubling passenger capacity to 20,000 per hour before the 2026 World Cup matches at MetLife Stadium.

This cautionary narrative carries profound implications as the region pursues integration through initiatives like Penn Station Access, which aims to extend Metro-North service into Penn Station by 2028. The Gateway Program likewise addresses the fundamental capacity constraints that limited the Meadowlands service. Yet these infrastructure expansions alone cannot guarantee success without sustained operational commitment through inevitable fiscal cycles.

The Meadowlands train experiment revealed both the potential of regional rail integration and the formidable barriers—infrastructural, operational, and fiscal—that fragment America’s largest transit network. Its legacy persists not through ongoing operations but in the lessons offered for future integration efforts: technical coordination provides merely the foundation; sustainable service requires both adequate infrastructure and unwavering institutional commitment to weather inevitable financial contractions.

For the brief period when Connecticut passengers could traverse Hell Gate toward a Jets game with only a single transfer at Secaucus, the region’s transit boundaries momentarily softened. The initiative’s collapse illuminates why such coordination remains more aspiration than reality in American metropolitan transportation—where fiscal cycles routinely sever the operational threads connecting fragile experiments in regional mobility, long before structural limitations become decisive.

One Response

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2