How Philadelphia Built America’s First Through-Running Regional Rail System

Beneath Philadelphia’s streets runs a tunnel that quietly transformed the city’s transportation landscape. The Center City Commuter Connection (CCCC), completed in 1984, is just 1.7 miles long, but its influence stretches far beyond its length. By linking the once-disconnected networks of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company, the CCCC altered the city’s relationship with transit, reshaped its economy, and challenged long-standing assumptions about how urban rail should function. Its central premise was simple: trains should move through the city, not stop at its edges.

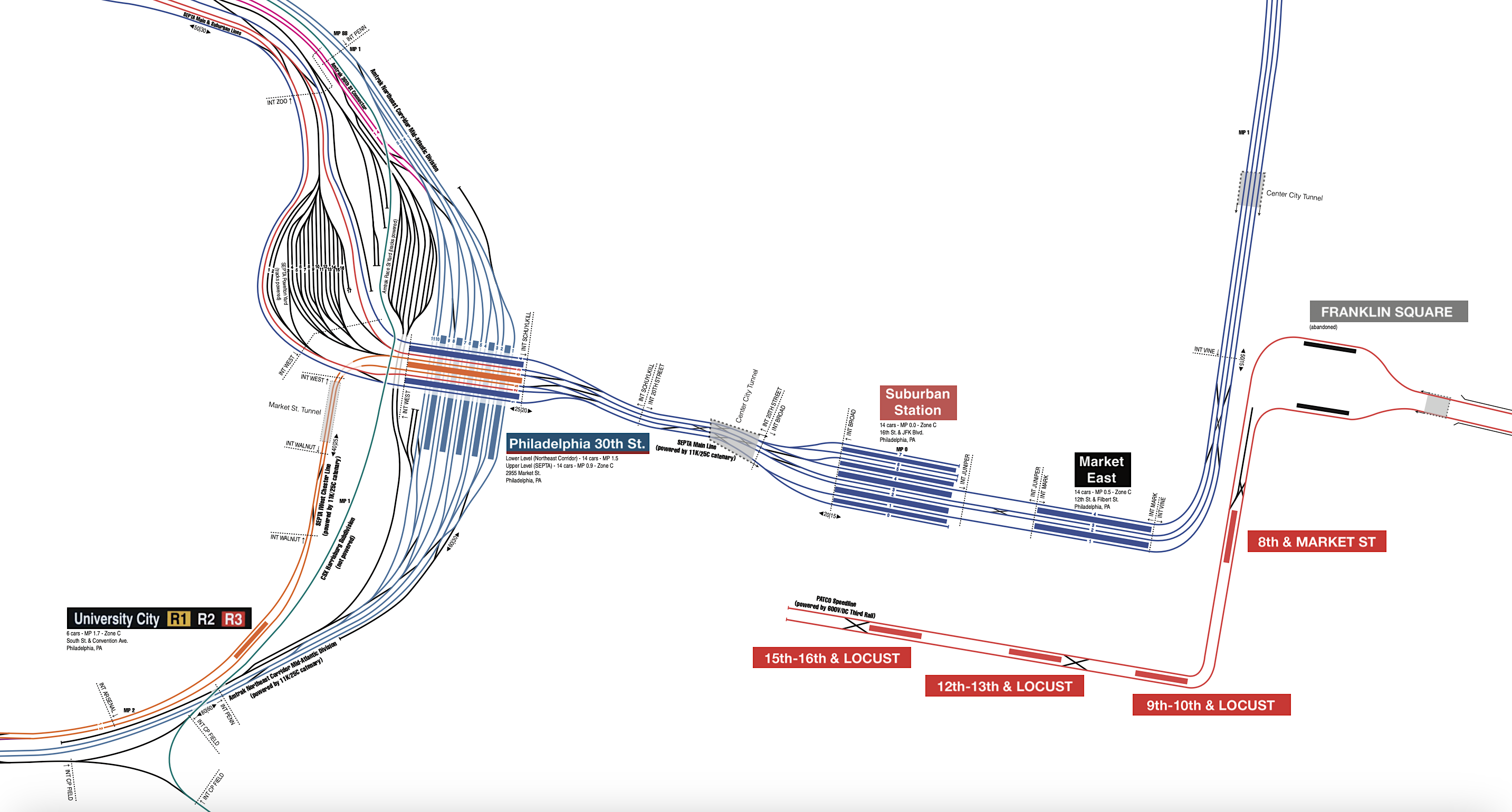

Philadelphia’s commuter rail system once reflected the legacy of 19th-century corporate rivalries more than the logic of modern urban mobility. The Pennsylvania Railroad terminated at Suburban Station and 30th Street Station, while the Reading Company’s trains ended at Reading Terminal. This arrangement forced passengers into unnecessary transfers, navigating city streets or underground passages just to continue their journeys. These disjointed connections imposed costs far beyond personal inconvenience. They limited regional access to jobs, reduced the efficiency of rail operations, and contributed to the stagnation of areas like Market East, which had once been a thriving commercial district.

The concept of linking the networks had been around since 1911, included in the city’s early comprehensive plans. But for decades, the idea remained on paper, lacking both political will and the necessary alignment of economic forces. By the 1960s, however, Market East’s decline was impossible to ignore. That’s when R. Damon Childs, a young planner with the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, recognized the problem wasn’t just with the trains. The city’s fractured rail system mirrored a fragmented urban economy. Childs proposed what seemed obvious yet had eluded action: build a tunnel to connect the lines, and the city’s fragmented spaces might reconnect as well.

Turning that vision into reality required more than technical expertise. It needed a political champion, and that role was filled by Mayor Frank Rizzo in the 1970s. Known for his forceful leadership style, Rizzo saw the project as an opportunity to leave a lasting mark on Philadelphia’s infrastructure. Construction began in 1978, backed by $330 million in funding—most of it from federal grants made possible through the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964. The project moved forward with an urgency rarely seen in large-scale urban infrastructure, driven by the belief that the city’s future depended on it.

Building the tunnel presented complex engineering challenges. The alignment cut beneath a densely developed urban core, threading through layers of aging infrastructure, active subway lines, and historic building foundations. The tunnel stretched from 30th Street Station under the Schuylkill River, curving beneath Philadelphia’s massive City Hall, and extending toward Spring Garden Street to meet the Reading network. Engineers employed a mix of construction techniques, from cut-and-cover excavation to deep tunneling, adjusting their approach based on the conditions above. The section under City Hall required extraordinary precision. Its massive masonry structure, one of the heaviest in the world, had to be supported during excavation using advanced underpinning methods like needle beams and grout injection stabilization. These techniques allowed crews to work safely beneath the city’s architectural centerpiece without compromising its stability.

While the engineering challenges were formidable, the social dynamics above ground added another layer of complexity. The tunnel’s path ran directly through Chinatown, raising concerns about displacement and disruption to local businesses. Community leaders pushed back, forcing the city to engage in negotiations that shaped both the project’s design and its construction timeline. Efforts to mitigate the impacts included altered construction schedules, noise reduction measures, and financial assistance for affected businesses. As part of these community negotiations, the city commissioned the Chinatown Friendship Arch, crafted by artisans from China. It remains a vibrant cultural landmark and a reminder that infrastructure projects don’t just reshape cities—they intersect with the lives and identities of the people who live in them.

Technical concerns didn’t end with construction logistics. Some critics questioned whether the tunnel’s 2.8% grade was too steep for the region’s existing commuter trains, particularly the older Reading Blueliner electric multiple units. Detractors predicted operational failures, arguing that trains would struggle to climb the incline. When the tunnel opened, these concerns faded. The Blueliners performed without issue, easily handling the grade and proving that cautious assumptions about technical limitations often underestimate the adaptability of well-designed systems.

The operational impact of the CCCC was immediate. Through-running service—trains traveling directly from one side of the city to the other without terminating—eliminated inefficiencies that had long plagued Philadelphia’s rail system. The number of trains needed to maintain service levels dropped by more than half, while crew hours were significantly reduced. The system no longer required empty trains to make “deadhead” trips just to reposition for the next run. These changes lowered costs, improved reliability, and allowed for more frequent service, creating a transit network that better matched the rhythms of the city it served.

Ridership increased sharply following the tunnel’s opening, with regional rail seeing a 20% jump in the first year alone. Commute times dropped, not by dramatic margins, but enough to matter—a reduction of around 15 minutes per trip. These time savings, multiplied across thousands of daily passengers, had a meaningful effect on quality of life and productivity. The tunnel also expanded access to suburban job centers, supporting the growth of reverse commuting patterns that were previously impractical. For many, the CCCC didn’t just make existing trips easier; it made new kinds of trips possible.

Above ground, the tunnel’s influence reshaped Philadelphia’s urban core. The construction of Market East Station, now Jefferson Station, became a catalyst for the revival of a neglected part of the city. The once-declining Reading Terminal Market was revitalized, preserving an essential part of Philadelphia’s cultural fabric while drawing new generations of residents and visitors. The Pennsylvania Convention Center, which opened nearby in 1993, anchored additional development, reinforcing the corridor’s role as a hub of economic activity. The city benefited financially as well, with real estate values rising and tax revenues increasing by more than $20 million annually. These gains weren’t isolated to transit-related metrics—they reflected the broader economic vitality that comes when infrastructure supports, rather than constrains, urban life.

While Philadelphia succeeded in implementing through-running, other American cities have struggled to replicate its model. In Munich, the S-Bahn’s central tunnel handles 30 trains per hour in each direction on just two tracks. Philadelphia’s four-track CCCC operates below that level, not due to physical constraints, but because of outdated scheduling practices and fragmented operational management. The tunnel’s potential remains underutilized, a reminder that infrastructure projects don’t end with construction. Their value depends on continuous adaptation to meet evolving needs.

Through-running rail service, as demonstrated by the CCCC, enhances more than transportation efficiency. It connects people to opportunities, reduces environmental impacts by encouraging transit over car travel, and supports more resilient urban economies. The CCCC’s success wasn’t inevitable. It required visionary planning, political commitment, and technical expertise, but it also required an ongoing willingness to challenge assumptions and adapt to new realities.

Philadelphia built the tunnel, but the work didn’t stop there. Its infrastructure holds lessons not because it’s a relic of past ambition, but because it continues to shape the present. The CCCC shows how a city can change when it refuses to accept fragmentation as the default. The challenge now is to build on that foundation—to treat infrastructure not as a static achievement, but as a living part of the city’s future.

One Response

Are you looking for a personal assistant who can handle your daily business operations and make your life easier? I can help with tasks related to admin, marketing, gathering data from multiple websites, answering emails, website management, social media, content writing, planning new projects, bookkeeping, entering data into softwares, and back-office assistance. I have an Inhouse Content writer, social media specialist, Data Entry Operator, Website Developer and Bookkeeper. My costing varies from $8/hr to $30/hr depending on type of project and its complexity.

If you are interested, send me an email at Businessgrowtogether@outlook.com with a list of tasks you want to accomplish, and We can discuss our collaboration over a video call as per your convenience.