Tunnel Under Park Ave. Urged to Link All Rail Lines

By NEAL PATTERSON

A new proposal to meet New York's tristate metropolitan area's tightening commuter problem by integrating a network of existing rail lines to serve commuter and suburban travel needs was advanced yesterday.

Sidney H. Bingham, railroad consultant and former boss of New York's subways, offered the plan to governors of the three states, city officials and railroad executives.

It's the only way, he suggested, to beat the ever-increasing clogging of highways by autos, with their insatiable need for more and more highway construction.

A New Rail Link

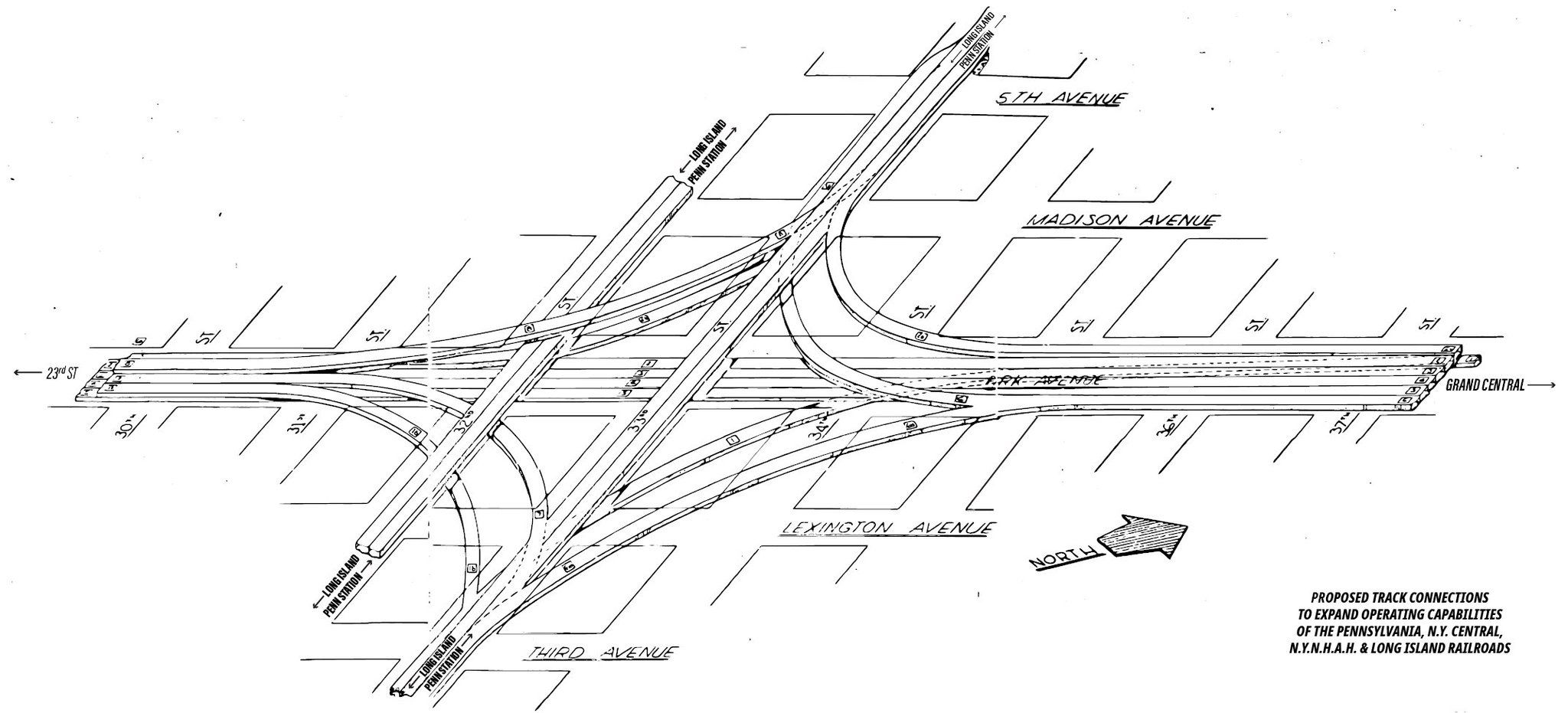

A key feature of Bingham's plan—which goes far beyond a previous one he put forward three years ago—is the construction of a tunnel under Park Ave. to connect lower level trackage of Grand Central Terminal with the Pennsylvania Long Island tracks under 32d and 33d.

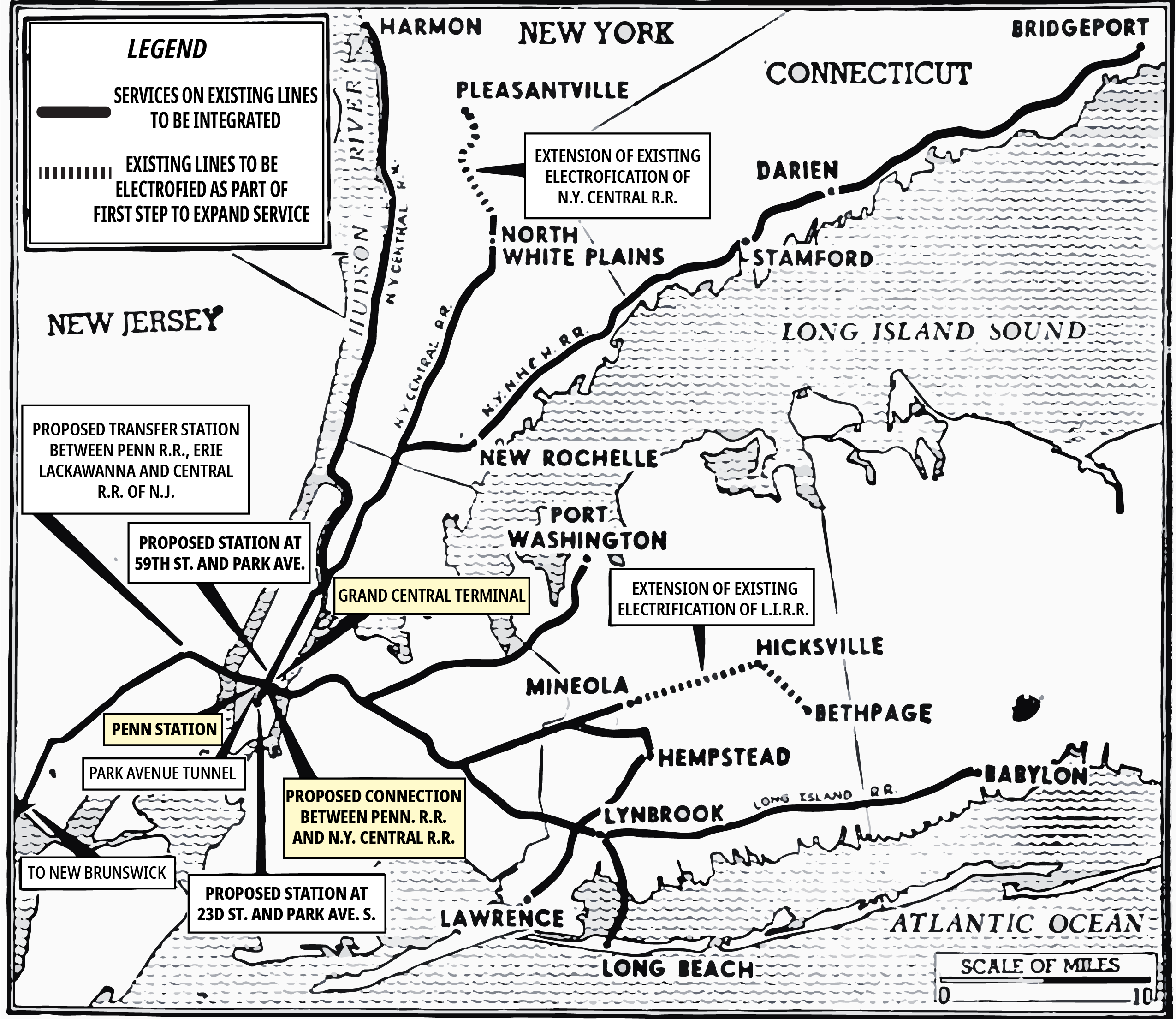

That connection, Bingham pointed out, would make possible the linkage into an integrated network of the four major commuting lines entering New York City—the New York Central, New Haven, Pennsylvania and Long Island.

He envisioned it as making possible "a single continuous transportation system" for riders from Long Island and Westchester in New York, Fairfield County in Connecticut and Union and Middlesex Counties in New Jersey.

As extensions of electrification are made, the transportation services would be expanded later to additional wide areas. Some of the railway long lines also could be combined into the system, Bingham said, and the direct route between Washington and Boston would offer substantial savings in money and time.

"It could also be an economic factor," he stated, "in making available a comprehensive system of fast transportation to and between the airports in the greater metropolitan area."

The tunnel link between Grand Central and Penn Station, he noted, would make possible the provision of stations at 23d St. and Park Ave. South and at 59th St. and Park Ave. Congestion in Penn Station and Grand Central would be lightened, due to passengers continuing on to these new stations, Bingham declared.

Total Cost $631 Million

He estimated construction costs at $138 million, but pointed out this is "but a fraction of the investment which would be necessary to provide, by other methods, a comparable public service."

New cars would cost an estimated $148.2 million more. Bingham placed the expense of possible railroad easements at an additional $345 million if the integrated system is to be operated by an independent company. Total $631.2 million.

Further steps, not included in his initial cost figures, might include establishment of facilities at Marian Transfer, in New Jersey, to provide connections for the Erie-Lackawanna and Jersey Central with the Pennsylvania; electrification of the Long Island to Hicksville and Bethpage; and extension of the New York Central's Harlem Division electrification from North White Plains to Pleasantville.

Bingham pointed out that approximately 16 million persons, or one-tenth of the nation's population, live in the tri-state metropolitan area and that estimates are another 6 million will be added by 1965.

Buried on page 16C of the New York Sunday News from May 19, 1963—just months before Pennsylvania Station met its demise—sits an article with the headline: “Tunnel Under Park Ave. Urged to Link All Rail Lines.” The paper is yellowed now, the kind of artifact you’d find in a library’s microfilm collection if you knew to look for it.

What emerges from those forgotten columns isn’t just another urban planning proposal lost to time. It’s a blueprint for the New York we never got, and proof that the daily nightmare of Penn Station represents sixty years of deliberate choices, not inevitable circumstances.

Sidney H. Bingham, former head of New York’s subway system, laid out his vision with startling clarity. Connect Grand Central Terminal’s tracks with Penn Station through a new tunnel, creating “a single continuous transportation system” that would unite the region’s four major commuter railroads. The projected cost: $138 million, roughly $1.4 billion in today’s money—a fraction of what current proposals demand. His rationale was simple enough: combat the “ever-increasing clogging of highways” by building the integrated rail network that transit advocates still beg for today.

Bingham’s plan reads like correspondence from a parallel universe where common sense prevailed. He described new stations to ease crowding, connections reaching the region’s airports, and the foundation for a genuinely world-class transit system. The vision wasn’t particularly exotic—just logical.

What followed instead was six decades of precisely the opposite approach. Regional leaders chose fragmentation over connection, brute-force expansion over operational intelligence. The Gateway Program’s current multi-billion-dollar plan for “Penn Station South” exemplifies this philosophy: build a massive dead-end terminal annex that amplifies rather than solves the station’s core design failure. It’s not progress; it’s the expensive institutionalization of dysfunction.

For years, railroad officials have dismissed through-running concepts like Bingham’s as fantasy, citing technical complexities, operational incompatibilities, and political impossibilities that supposedly make such integration unworkable.

This is where their credibility collapses entirely.

From 2009 to 2016, they operated the “Train to the Game”—a direct service connecting Connecticut to New Jersey’s Meadowlands through Penn Station. Not a brief experiment, but an eight-year demonstration of precisely the kind of regional integration officials claim is impossible. The service originated on Metro-North’s New Haven Line, switched to Amtrak’s Hell Gate Line at New Rochelle, crossed the Hell Gate Bridge through Queens and the Bronx, entered Penn Station for crew changes, then continued through the North River Tunnels to Secaucus Junction. Passengers traveled on a single ticket across three states, three railroad systems, and multiple power configurations.

The operational complexity was extraordinary. NJ Transit’s dual-voltage trainsets had to function across incompatible electrical systems. Crews changed at Penn Station with precisely timed ten-minute transfers. The service navigated union agreements, territorial boundaries, and equipment specifications that supposedly create insurmountable barriers to through-running. Metro-North crews were specially trained on NJ Transit equipment. Detailed memoranda governed everything from equipment leasing costs to dwell times.

In its inaugural 2009 season, the service ran three trains each direction for nine games, carrying 5,826 passengers and generating $67,727 in revenue. The most popular train consistently arrived ninety minutes before kickoff, demonstrating that passengers valued the convenience enough to plan around the schedule. The service proved sustainable enough to continue for seven additional years, even after being scaled back to one train each direction.

The railroads demonstrated they could solve integration puzzles when properly motivated. They managed crew coordination across agency boundaries, equipment compatibility across power systems, and fare integration across separate bureaucracies. Every technical barrier, every operational challenge, every institutional obstacle that officials cite as reasons why regional through-running remains impossible was successfully addressed for football fans traveling to Sunday games.

The service eventually declined not because of technical failures but because of reduced frequency and competition from driving. When service dropped from three trains to one after 2009, utility plummeted. The lesson isn’t that through-running doesn’t work—it’s that sustained political commitment and adequate service levels are required to compete with existing travel patterns.

That 1963 newspaper clipping becomes more than historical curiosity—it’s evidence of a crime scene. Every official pronouncement about technical impossibility, every bloated budget for expansion projects that ignore the fundamental problem, every press conference about infrastructure modernization carries the weight of Bingham’s ghost and the eight-year proof of concept that followed.

The solution has been documented for over half a century and demonstrated for nearly a decade. We can have the “single continuous transportation system” Bingham outlined, or we can endure another sixty years of expensive, willful dysfunction. The railroads already proved what’s achievable when properly motivated. The next time officials claim integration is impossible, remind them they operated it successfully for eight years—and ask why 600,000 daily commuters deserve less consideration than weekend football crowds.