Revisiting the Ghosts of an Unfinished Vision

There are places around the New York metropolitan region where silence does the talking. Rusting rail spurs cling to the edges of shuttered factories, vestiges of a once-thriving industrial engine. Overgrown lots remain stubbornly vacant, testament to ambitious housing projects that never broke ground. Even the highways, conceived in a different era, carry a muffled roar that speaks less to future aspirations than to a bygone age. All these landscapes whisper of a deeper absence—the missing architecture of a coherent regional governance system capable of stitching together solutions that don’t stop at state or county lines.

Over four decades ago, an experiment in precisely such a system flickered and then died: the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission. Its roots were specific—conjured by mid-century optimism about technical mastery and the swelling postwar metropolis—yet its demise speaks to enduring political fault lines. The Commission’s story is not a dull register of bureaucratic complexities; rather, it is a stark parable of American governance. It dramatizes the uneasy dance between local autonomy and regional necessity, between political short-termism and strategic vision, and between the illusions of parochial comfort and the hard truths of common destiny. At every turn, issues of race and class added turbulence, shaping who could live where and determining which communities thrived while others were left behind. In an era of intensifying storms—both literal and figurative—the cautionary tale of the Tri-State Commission feels more urgent than ever.

A Call from the Past

On October 11, 1987, with Connecticut’s withdrawal from Tri-State having hammered the final nail into the Commission’s coffin, Dr. William Ronan—former chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and a Port Authority board member—addressed a gathering of bankers and executives in White Plains. His plea for a return to regional consciousness rang with a certain nostalgia. He invoked the mid-century period when White Plains, Bridgeport, and Stamford were “foreseen—growing out of highway, rail, and other basic factors,” as if those former triumphs might galvanize a new generation. Ronan lamented a turn toward localism, supercharged by federal requirements for neighborhood-level approvals. The Commission, once the emblem of pragmatic cooperation, had been “terminated,” leaving behind a vacuum in regional planning that persists.

The Rise of Technocratic Optimism

In the mid-20th century, there was a near-utopian belief in planning. Backed by federal agencies, economists, engineers, and urban designers believed they could harness the postwar boom and the ascending automobile culture to build orderly, efficient metropolitan regions. The federal government, then enamored of large-scale problem-solving, encouraged these grand visions through housing and transportation programs. It was in this hopeful spirit that the Tri-State Transportation Committee was born in 1961, tasked initially with rescuing dying commuter railroads whose very survival transcended individual city or state boundaries.

Formalized as the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission in 1965 and widened in scope by 1971, this new body took on a daunting range of issues: not only transportation, but land use, housing, environmental concerns, and beyond. It drew upon a formidable pool of experts who occupied offices in the gleaming new World Trade Center, a physical symbol of the era’s ambition. Their studies yielded visionary proposals: an integrated network of clustered development, greater affordability in housing, and more environmentally sound land-use patterns. Dr. William Ronan was the chief prophet of this gospel—an unabashed believer in big infrastructure for a big metropolis. He advocated for a fourth jetport in Newburgh, a Long Island Sound bridge, and trans-Hudson crossings designed to knit the region together more tightly.

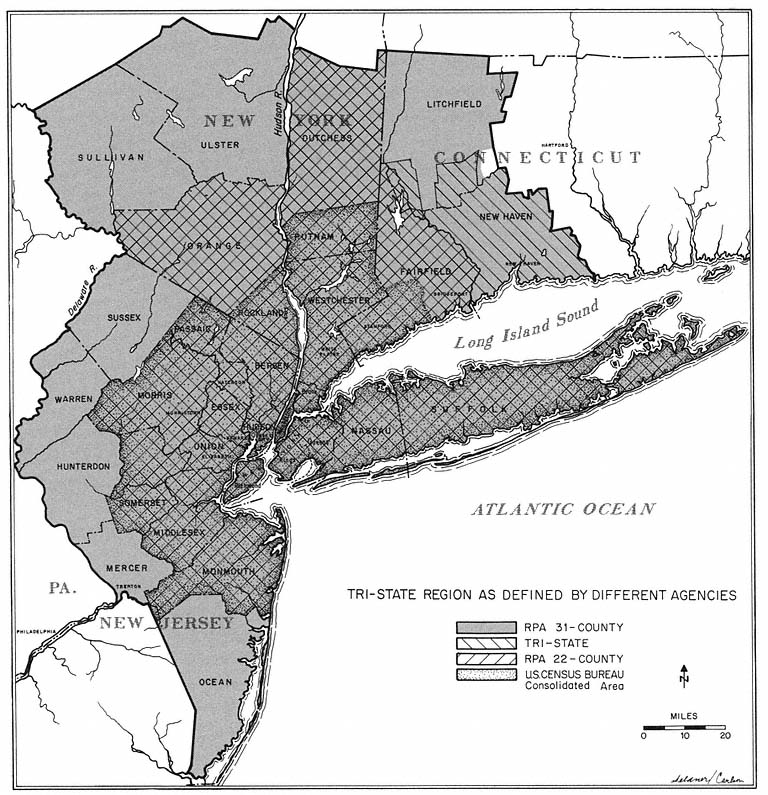

Unlike lofty concept papers, the Commission’s proposals were concrete: specific yearly housing targets to address substandard conditions, recommendations for higher density to discourage sprawl, a push for waterborne transportation in New York Harbor, and a host of technical interventions to modernize commuter lines. In effect, the Commission promised an encompassing plan. In theory, it stood ready to coordinate across three states and 27 counties, factoring in demographic trends and municipal needs under one roof.

A Terrain of Fragmented Loyalties

But the region’s mosaic was massive: more than 550 municipalities with divergent interests, each clinging to its own sense of sovereignty. Interconnections between city centers and suburban fringes were clear—on Long Island alone, commuters frequently spilled into Manhattan by the thousands—but those ties grew faint toward the region’s outer edges, where only a sliver of the workforce traveled regularly to the city. The Commission operated under the assumption that these multifarious zones, some deeply dependent on Manhattan’s economic engine, shared enough common ground to demand a unifying approach. The reality proved less cooperative.

Unlike the Port Authority, whose ability to levy tolls and build infrastructure carried genuine clout, Tri-State had no such enforcement powers. It could produce data, recommend policies, and attempt to mediate disputes, but it relied entirely on the voluntary goodwill of governors and local officials. The politics of “home rule” and local autonomy flourished in suburban hearts—particularly on Long Island, where Tri-State was derided as an out-of-touch meddler. Irritation grew so sharp that officials from Nassau and Suffolk counties openly proclaimed that the Commission had done them “no good, ever,” and demanded to be left alone to court federal grants independently.

Connecticut leaders were similarly vexed. State Senator Wayne A. Baker of Danbury questioned the premise of endless planning: “Why are the cities dying? I don’t know, but these guys will draw up plans until you’re blind,” he said, reflecting a wider suspicion that Tri-State was an incorrigible paper machine. Nor did New Jersey remain silent. Critics described the Commission as irrelevant, repetitive, and unaccountable. Even Tri-State’s own executive director conceded that it had become a “paper-pushing rhinoceros.”

Meanwhile, the Commission’s governance structure itself sowed dysfunction. Because each state appointed commissioners and no action could move forward without simultaneous approval from New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut representatives, any single holdout could render the entire body inert. To make matters worse, absenteeism among these political appointees was rampant. Mayors who rarely—or never—attended Commission meetings could effectively stonewall decisions, deepening the sense that Tri-State lacked both legitimacy and real impact.

The Thorn of Housing

As if the governance deficits weren’t enough, the Commission collided with an even deeper taboo: suburban hostility toward affordable housing. Under the banner of regional equity, Tri-State’s plans proposed spreading low- and moderate-income housing beyond city limits, dispersing it into the very neighborhoods whose residents had often fled urban centers in pursuit of exclusivity. Though rarely stated openly, the pushback was fraught with racial and class anxieties. From Long Island to Westchester, public debate simmered with references to preserving “community character” and “property values.” Underneath the coded language lay the fear that integration might reorder the careful segregation upon which entire suburban enclaves rested.

When Tri-State introduced a housing plan in 1977 that would have increased density mandates and challenged restrictive zoning, suburban commissioners and local officials were so alarmed that four of New York’s five delegates simply abstained from the vote, blocking the measure. Newspapers at the time captured raw sentiments from suburban leaders who interpreted the Commission’s stance as an overreach, and, in some corners, an existential threat. As momentum drained away, the Commission never recovered from the political fallout of urging integration in communities fiercely devoted to local prerogatives.

Waning Federal Winds

Tri-State’s frailties coincided with a national political shift. Funding streams that once enabled ambitious planning began to dry up. The Reagan administration’s turn toward deregulation and budget austerity gutted large swaths of federal support for the kind of multi-state collaboration the Commission embodied. Suddenly, Tri-State was losing millions in potential grants, eroding its capacity to produce reports and limiting its ability to coordinate with local governments. Without the gravitational pull of federal dollars, the Commission discovered it had precious little leverage.

In 1981, a task force commissioned by the governors of the three states attempted to salvage Tri-State’s mission with reforms. They recommended streamlining the Commission’s structure, amplifying its focus on strategic issues, and engaging the public to restore legitimacy. Even more drastic suggestions floated around—such as trimming its vast jurisdiction to exclude “outer” areas with tenuous commuting ties to the core. But with Connecticut resolute in its decision to leave, these reforms arrived too late to prevent the inevitable. By mid-1982, the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission had dissolved, leaving behind an empty suite of offices in the World Trade Center and, more significantly, an institutional void in regional governance.

The Costs of Collapse

The ramifications of Tri-State’s demise remain palpable. Transportation in the region became (and remains) a tangled web of agencies—NYMTC, the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, and separate bodies in Connecticut—each confined to a sliver of the larger puzzle. Fare structures are incompatible, infrastructure is patchily funded, and an insidious parochialism persists. Meanwhile, exclusionary housing policies continue to aggravate inequality. Many suburban municipalities never established the affordable units that Commission reports had once urged, and the scarcity of housing near job hubs keeps commutes long and property values artificially high.

If Tri-State had persisted, perhaps the region would have navigated climate resilience more cohesively. Rising sea levels, more frequent storms, and overburdened infrastructure require a strategy that spans state boundaries—just as air pollution or water supply crises do. Instead, a patchwork of smaller authorities and ad hoc initiatives addresses urgent issues fitfully, lacking a unifying blueprint or a centralized authority to muster the necessary resources.

Such fragmentation places the New York region at an economic disadvantage relative to metropolitan areas—domestic and global—where coherent regional governance bolsters competitiveness. From the Minneapolis–St. Paul Metropolitan Council to Portland’s Metro, other regions have found ways to tax-base share, unify transit operations, and coordinate land use. These models underscore what might have been possible: permanent bodies with dedicated funding and at least a measure of authority to override local decisions on matters of genuinely regional concern.

Learning from Tri-State’s Failure

Any future attempt at building a new regional framework must take Tri-State’s lessons to heart. Indeed, the Commission’s downfall highlights the perils of insufficient power: a planning agency that can only advise is easily disregarded by localities, while an agency that can overrule local governments without democratic legitimacy becomes a lightning rod for resentment. Tri-State’s top-down structure, appointed commissioners, and reliance on federal funds all combined to alienate local officials who felt threatened rather than included.

For a new entity to succeed, it must be clearly defined in scope—focusing on cross-boundary imperatives such as comprehensive transit networks, climate adaptation, and equitable housing. It must secure an independent revenue stream, so it does not collapse whenever political winds shift. Most critically, it must be accountable, whether through direct elections or balanced representation of local governments that ensures the voice of communities is genuinely heard. The fervent opposition that doomed Tri-State was only partly a matter of reflexive localism; it was also a protest against an unwieldy layer of governance with uncertain legitimacy.

Regional advocates should also acknowledge that robust planning requires confronting racial and class disparities openly. Tri-State’s aborted forays into affordable housing signaled an intention to chip away at patterns of segregation, but the Commission was ill-prepared to handle the political blowback. A future agency would need a more deft and transparent strategy—one that invites, rather than compels, suburban municipalities to share responsibility for addressing the region’s most pressing social and economic challenges.

Toward a Shared Tomorrow

In the decades since Tri-State’s dissolution, various piecemeal alliances have emerged, from environmental coalitions focusing on shared water resources to local councils of government handling corridor-level planning. Non-governmental groups like the Regional Plan Association (RPA) have tried to fill the vacuum, releasing ambitious blueprints and convening stakeholders. Yet none of these efforts possess the binding power that a resilient regional commission might wield.

Ironically, the very forces that once dismantled Tri-State—pressures for local autonomy, the complexities of interstate rivalries—have also intensified the region’s problems. The silence hanging over disused rail spurs and overgrown lots is not merely the hush of industrial decline; it is the reverberation of lost opportunity. So long as climate threats deepen and housing remains scarce, so long as highways choke with traffic and cross-state competition saps resources, the region will continue to pay for its fragmentation.

The question, then, is not whether the New York metropolitan area needs a revival of regional thinking but how to achieve it without replicating past missteps. The Commission’s ghost is a reminder of the pitfalls: structural vulnerability, democratic deficits, ingrained parochialism. But it also stands as a testament to the daring vision that once united an archipelago of governments. In that sense, the Tri-State story is not a mere cautionary tale of hubris undone; it is an unfulfilled promise, pointing to the possibility that, somewhere in this vast metropolis, a keener sense of shared fate can still be forged.

Without that unifying ethos, the region remains an extraordinary metropolis hobbled by artificial boundaries and stunted collaboration. Yet if public will, political courage, and institutional savvy can align, the dream of genuine regional governance might yet be realized—just as Dr. William Ronan envisioned decades ago, urging leaders in White Plains to see beyond the dividing lines on a map. Only then will the silence of those rusting rail spurs give way to the hum of renewed possibility—heralding a future in which each community recognizes that its fortunes, for better or worse, are inextricably linked to all the rest.